I flew to Russia via a stopover in Belgrade. There was a civil war going on which explained the cut price Yugoslav Airlines fare, though the saving was lost when I was robbed in a sleazy Belgrade hotel. Undaunted, next day I touched down at Sheremetyevo airport, Moscow. It was Sunday, 1 December 1991.

I flew to Russia via a stopover in Belgrade. There was a civil war going on which explained the cut price Yugoslav Airlines fare, though the saving was lost when I was robbed in a sleazy Belgrade hotel. Undaunted, next day I touched down at Sheremetyevo airport, Moscow. It was Sunday, 1 December 1991.

I’d been diligently studying Russian Politics for years but with the fall of the Berlin wall and the collapse of communism Sovietology had become redundant overnight. Time has blunted the sweetness of the West’s defeat of the Evil Empire. Our financial and economic crises, to which the USSR was always immune, continue. And the statistic that 85 guys today own as much wealth as half of the planet is not one you’ll find advertised in neon on Times Square any time soon. But when I arrived the whole system was in chaos.

Gorby was gone, Yeltsin was in and the Party – the communist one – was over. Only its iconography remained – groovy Soviet era posters and badges, fur hats, babushka dolls and samovars. Such memorabilia can only be found nowadays, so I’m told, in trendy Moscow cafes. But every war veteran with one leg was out selling his campaign medals in 1992. During my stay I snaffled up as much as I could; the spoils got packed up, posted, and duly stolen en route home.

I got picked up at Sheremetyevo by a retired Army Colonel, Boris. He was ex-Rockets – the ICBM type ones that were (and presumably still are) pointed at threats to Russian civilisation such as Paris, Washington and Auckland. We drove through near deserted streets in the grey light of winter dodging pot-holes big enough to swallow our entire car. They still hadn’t tidied up the burnt out APC’s cluttering the Ring road, left over from the previous August’s coup.

Our destination was one of the coveted ‘Stalin’ apartments built in the 1930’s near the Kievskaya metro, where Boris’ wife, Ekaterina, awaited with a traditional welcome of tea plus some bread we’d bought on the way. Two bedroomed and high ceilinged their apartment was hardly spacious, but here Boris and his wife had raised two children, and now lived with their German Bulldog named Geezi (after the German foreign minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher). Décor, furniture and fittings were frozen in retro 1965. The second bedroom had long been a library, and I bedded down on that Soviet stalwart – the fold out sofa – surrounded by hundreds of musty and invigorating leather bound tomes such as the Combined Soviet Almanac of Engineering.

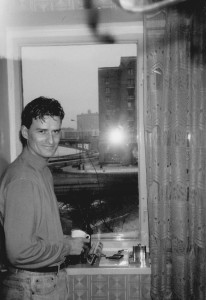

The next morning I had to wait till 10am for a watery dawn and a view out my bedroom window. The emerging skyline was a Dickens novel come to life: a mix of industrial and residential with a cluster of bulbous onion domes denoting a church tucked away somewhere between smoke stacks and a children’s playground. The traffic, such as it was, crawled through a brown slush of dirty snow: buses, trucks, taxis, and the odd private car. The trucks were all a uniform 1950’s US Bedford style, ready in an instant to be converted into Infantry lorries when World War III broke out.

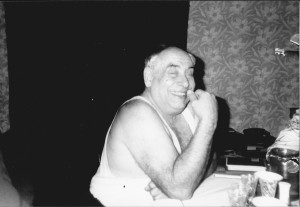

Boris entered my bedroom in a singlet and y-fronts gripping a meat cleaver. I feared the worst. Nothing much had stuck from my six week Russian Language immersion course but I hit him with ‘Previet. Ya doorak.’ My Russian friend Grischa had drilled this greeting into me at Melbourne airport before my flight. Boris just shrugged and pushed past me. It turned out that the family’s winter stash of meat was chained and padlocked in a sack on my balcony: a cut price Moscow freezer.

I repeated my phrase ‘Previet. Ya doorak’ confidently to everyone I met for the next two weeks until a kindly English/ Russian speaker told me it actually meant ‘Hi, I’m a moron.’

My adventures had only just begun…